in defence of food security

This week, we have a response to last week's newsletter about farming. It's from someone well placed to understand the issues facing the sector - a former farmer, now a general manager at a food-transporting logistics company. Over to him...

Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) subsidies

"The much-maligned CAP has been a success by most measures – as you state, it has reduced the proportion of net disposable income spent on food almost year on year since its inception. It stimulated increased productivity and gave food security that had not been seen before (we still had rationing in Britain up to 2 years before I was born).

There were downsides but this turned out to be a great deal for consumers and played a part in improving overall living standards. Don’t underestimate the level of poverty that existed in Britain in the 1950s and 60s. The CAP acted as a food insurance policy – you pay in (subsidies) but it protects you from disaster (food shortages) – if you are hungry you will pay any price for a loaf of bread, but for the last 40 years we have had bulging supermarket shelves.

That does not take away from the fact that it will need to evolve to reflect changing circumstances, but I would bet people will look back in years to come and think it was not so bad. If other policies had been as successful e.g. transport, we would have regular affordable uncrowded commuter services (but we would probably moan that vast areas were covered by expensive subsidised rail lines)."

Ruminants

"Ruminants are reared on large areas of the UK, as you say, because the land cannot be put to any other use. Mountainous areas, moorland, dales and valleys cannot be cultivated but grow good grass that can be turned into food and that will still make sense for a long time.

We should not be complacent about food supplies especially with the effects of climate change and global politics, which can easily disrupt supply chains.

My view is that we should use science and technology to lower the impact of methane emissions – for instance, there is evidence that seaweed supplements in ruminant diets will reduce the amount of methane an animal produces. Therefore, it would make sense to direct resources into research to help maintain these very efficient grass converters.

I also think that grassland does absorb carbon from the atmosphere and grazing animals return natural organic fertility to the soil in a natural cycle, making it more carbon absorbent.

A separate environmental benefit of ruminants is that they are excellent re-cyclers of waste product. Take the alcohol industry as an example – large volumes of cereals are grown in the UK specifically for the brewing and distilling industries. As a result, they produce a corresponding amount of spent grains as part of the process. These are high in protein (the sugars have been turned into alcohol) and make a very good balanced feed for cattle and sheep.

The alternative would be to burn or use in an anaerobic digester – if the infrastructure is not there, it could end up in landfill. This applies to many food products – citrus pulp, oilseed husks, sugar beet pulp, cider apple pulp, potato and vegetable waste among others. These products have been recycled for many years before recycling was sexy, and form part of a sustainable food production system which has a great many balancing factors."

Arable technology

"Modern arable farmers – particularly the larger scale ones are already ahead of the curve in soil management and sustainable farming.

Technology and larger powered machinery have allowed a move into no ploughing for a large proportion of combinable crops. Following harvest, crop residues are chopped and mixed into the soil (rather than turning it over with a plough and releasing carbon into the atmosphere). Big horsepower also allows deep tine aeration and satellite mapped tramlines, which reduce compaction and improve soil structure.

I think you will find many modern arable farms are improving their soils and showing high organic matter and strong worm activity. The way forward is to use technology and science to improve further: more science, more technology more productivity, healthier soil - sustainable farming.

Sorry, I could go on a long time, but I think the main thing is to be open minded but not complacent - my own predictions below.

Prediction 1 is that commercial reality will dictate the move to larger, more efficient farms as the benefits of scale increase. There will always be many variables – Prince Charles, I am sure, classes himself as a farmer as does James Dyson, but their challenges are very different to a tenant on a medium sized family farm.

There has been a natural polarisation for many years with smaller holdings being turned into hobby farms (to be seen on TV most nights) and medium sized units getting consolidated, usually when a family member dies or retires and there is no successor. Larger farms will get larger and small farms will exist but will be non commercial in farming viability.

Prediction 2 is that there will be moves to re-wilding as there already are, but we will settle with a good old British compromise somewhere in the middle.

Prediction 3 is that cattle and sheep numbers will drop gradually as land is put to other uses – a lot for sport and recreation, but we will be importing more beef and lamb from Aus, NZ and S America.

Prediction 4 is that we will experience real food shortages within the next generation – many factors increasing the risk – and this will lead to further change in the way we manage land."

Harvest in Indian Head, Saskatchewan, Canada. Photo by Dan Loran on Unsplash.

a question of priorities

Our different perspectives stem, I think, from different priorities (and my ignorance!). If we accept that climate change will cause profound instability - famines in the global south, shocks to global supply chains, and huge migrations of people to temperate nations - then what’s the best response to that challenge? Do you focus on strengthening food security or reducing emissions?

The arguments mirror one another:

Food security as top priority: Global warming will cause massive global instability. This instability will affect global food supply. Therefore, we need to do everything we can to maintain food security at home. Reducing our emissions must play second fiddle to our food security, and so ruminants will remain a central part of our food supply. Advances in farming technologies will hopefully solve the emissions problem.

Emissions as top priority: Global warming will cause massive global instability. This instability will affect global food supply. Therefore, we need to do everything we can to reduce our emissions as quickly as possible in order to help avoid this global instability. Food security at home must play second fiddle to reducing emissions, and so ruminants cannot remain a central part of our food supply. Advances in farming technologies will hopefully solve the food security problem.

You can project these arguments onto many other policy areas (e.g., energy). In each case, you have to reckon with the same question: if climate change is a clear and present danger, should I prioritise (i) the reduction of emissions or (ii) measures that will help me weather that danger?

hatches: to batten or not to batten

The run-up to climate disaster is, then, analogous to the run-up to war. If you want to avoid war, then the sensible thing to do is to trade and engage more with your rival, to knit your two communities together with mutual obligations (this is what the EU is all about). And if you want to avoid climate disaster, the sensible thing to do is to reduce your emissions.

But both of those things - trading more with your rivals and reducing emissions - require you to think that the bad thing (war / climate disaster) can be averted. If you think that the bad thing will probably happen, then your priority should be to prepare your country for living with that bad outcome, and so:

- Instead of importing e.g. steel from your rival, you focus on producing steel at home. After all, if war breaks out with your rival, you can't rely on them for steel! But in stopping this trade, you remove the mutual obligations that bind you to your rival, and you make war even more likely. Oh no!

- Instead of focusing on reducing emissions, you focus on making your country as climate change-proof as possible. You increase domestic food supply. You increase domestic energy supply. But in doing those things, you make climate disaster more likely. Oh no!

The way around all this is to do things that both cut emissions and prepare us for a world of climate change-induced shocks. e.g.

Increasing domestic energy production via renewables so that we are less exposed to crises in global oil & gas supply.

Reducing domestic energy consumption (e.g. insulation, behavioural changes) so that, again, we are less exposed to crises in global oil & gas supply.

Reducing the amount of calories that we consume so that food security can be achieved more easily. The average Briton (myself included) consumes c.500 excess calories per day. Across the country, that's 35 billion excess calories per day and c. 13 trillion per year. We can measure this calorific excess in acres of wheat. If an acre of wheat produces 4 million calories per year, then it would take c.3 million acres of wheat to produce our calorific excess, which amounts to 36% of all arable farmland in the UK, or an area the size of Norfolk and Lincolnshire combined. Remove these excess calories and you lower the height of the hurdle that we have to clear to achieve food security.

How do you make the Rt. Hon. Mark Francois MP care about climate policy?

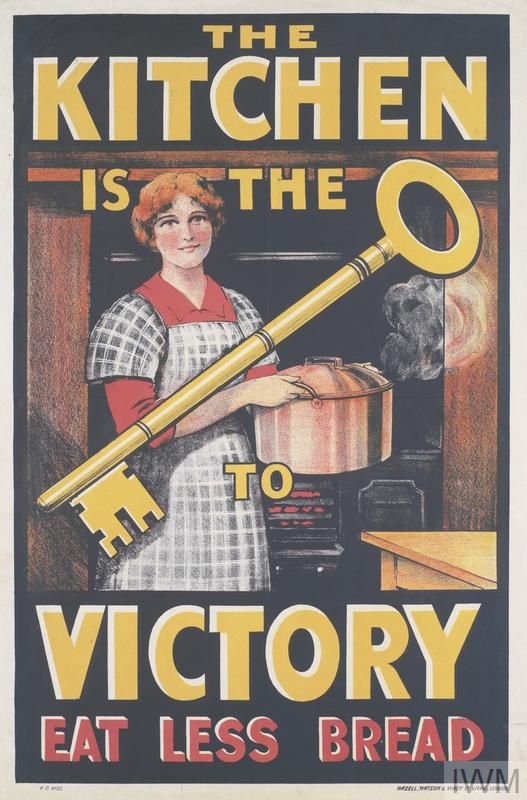

All this talk about food/energy security and acres of wheat is quite vintage stuff. It's the language of war cabinets. Perhaps this is how you get sceptical Conservative MPs on board with radical climate policy: tell them it's like the Second World War. Once again, we must prepare our economy to stand alone, and we must exercise our peculiar talent for restraint, parsimony, and self-reliance. etc.

© IWM Art.IWM PST 6541

it'll be fine-ism

You've had a lot of doomsterism from me this week, sorry!

Some optimism: most of the above is premised upon climate change causing significant supply chain disruption. The lesson from Covid has been that global supply chains are much more resilient than we think. The supply chain disaster that many were predicting in 2020 never really materialised. So: it'll all be okay... maybe.

If you've enjoyed this newsletter, please forward it on.

If these emails are going to your spam, then either add my email (charlie@re-working.co.uk) as a safe sender, or reply to this email (feedback welcome).

And if you aren't yet subscribed, please subscribe to receive the weekly newsletter. Thanks!